Preface

Preface

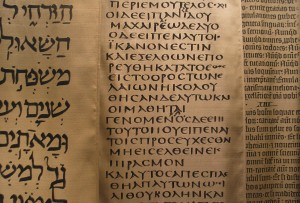

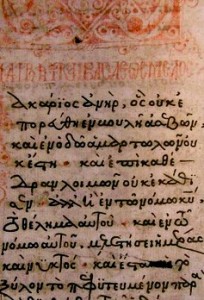

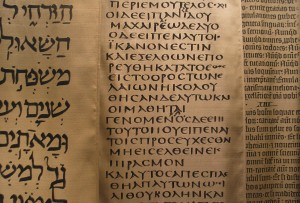

The purpose of these articles was to explain to our faithful, in a simple and easily-understood manner, some of the differences that exist between the Old Testament (Masoretic) text used by most of today’s Roman Catholics and Protestants and the Septuagint Old Testament used by Orthodox Christians since the time of Christ. All told, there are some 300 textual differences between the Masoretic and the Septuagint texts, some of them important and some of them insignificant.

These articles will explain why Orthodox Christians prefer the Septuagint, despite some admittedly beautiful and eloquent passages found in the Masoretic text. The articles by Metropolitan Ephraim were originally published on the internet in the Spring of 2009, and they appear here in a slightly edited and augmented form.

1. HONOUR THE PHYSICIAN

In the Wisdom of Sirach, it says:

“Honour the physician with the honour due unto him for the uses ye may have of him: for the Lord created him…The skill of the physician shall lift up his head, and inthe sight of great men he shall be in admiration. The Lord hath created medicines out of the earth, and he that is wise will not abhor them…And the Lord hath given men skill, that He might be honoured in His marvelous works. With such doth [the physician] heal men, and taketh away their pains. Of such doth the apothecary make a confection; and of his works there is no end; and from him is peace over all the earth” (Wisdom of Sirach 38:1-8).

When I was a little boy of about seven or eight years of age back in California, one of my playmates [who was Protestant] asked me if I wanted to come over to his house that night for a Bible class. Since my mother often read me Bible stories, and I liked them, I was very much inclined to go to my friend’s house that evening. But first, I had to get Mom’s permission. Faster than it can be told, I ran home to get Mom’s okay. She listened as I recounted my buddy’s invitation, and she could see that I was obviously excited about it. Then she nodded her head in a negative way, and said,

“No, I don’t think so. You see, son, they don’t use the same Bible we do.”

“Awww, nuts! Come on, Ma! It’ll be okay!” I persisted.

“No, I don’t think it will be okay. I’ll buy you a book with some Bible stories,” she concluded, firmly holding her ground.

I stomped out the back door, sulking and thinking to myself, “She only said that they don’t have the same Bible we do because she doesn’t want me to go to the Bible class.”

But Mom was right.

She was a simple woman. She had not had much of an education, but she was sharp as a tack [she had to be: she had given birth to seven male rapscallions, and it was only by expending desperate and superhuman efforts that she was able to prevent two of them, especially, from disrupting the entire neighborhood. She used to tell me, “If you had been a jackass when you were young, you would have died from the beatings you got!”] However, to return to the main thrust of our story.

She was right, of course, about the non-Orthodox having a different Bible. By the word “different,” she could have meant two things: 1] the actual books in the non-Orthodox Scriptures are different from those that we have in our Scriptures [true]; or 2] the Protestants and Roman Catholics interpret the books of the Holy Scripture differently than we do [also true]. The quotation that was used at the beginning of this article is a case in point. The Wisdom of Sirach [or Ecclesiasticus] is not found in the Protestant Bible, and the Roman Catholics call it “deuterocanonical,” [whatever that is]. The odd thing, however, is that, in our Saviour’s time, the Jewish people honored these texts as “Holy Scripture.” Proof of this are the many quotations from these holy books that can be found in the New Testament. Furthermore, if the Protestants had not rejected so many books of the Holy Scriptures, there might well have never arisen among them such strange nineteenth century sects as the so-called Christian Scientists, who, as we know, reject the use of human medicine — often with disastrous results.

After all, as clear as a bell, the Wisdom of Sirach teaches us:

“Honour the physician with the honour due unto him for the uses ye may have of him: for the Lord created him….”

There are other valuable teachings in these holy books, as well. For example, there is one prophetic text that, in less than fifty words, sums up the entire purpose of the Incarnation of the Son of God. In one sentence, in fact, it answers the question: why did God become man? This wonderful text is in the book, the Wisdom of Solomon, and in the clearest possible terms it tells us:

“While all things were in quiet silence, and the night was in the midst of her swift course, Thine almighty Word leaped out of Heaven out of Thy royal throne, as a fierce man of war, into the midst of a land of destruction.” (Wisdom of Solomon, 18:14-15)

We do, indeed, have a very different Bible from our non-Orthodox Christian friends.

Thanks, Mom.

2. THE NEUTRALIZATION OF THE NETHERWORLD

“Isn’t that what Adolph Hitler did to Holland in World War II?”

This, indeed, is the sort of reaction you might expect to get if you were speaking to someone about the “neutralization of the Netherworld.” He really wouldn’t know what you were talking about. On the other hand, if you were to refer to it as the “Harrowing of Hell,” people might or might not understand. Orthodox Christians know it as the “Descent into Hades.” Most “Bible-believing” Americans nowadays, however – even those living in the so-called Bible Belt – would probably look at you quizzically if you were to mention it – despite the fact that it is cited in the Holy Scriptures (I Peter 3:18-20).

Indeed, this is what happened on one occasion at our monastery in Boston. Perhaps thirty or so years ago, a Protestant minister and his wife were visiting the monastery and I was assigned to give them “the tour.” We had seen the workshops, the refectory, the chapel and finally came to the area where the icons were on display, and I was telling the couple that the monastery was self-supporting. “One of the ways we support our monastery is by producing and selling these icons,” I explained to them. They knew about the traditional use of the holy icons in the Orthodox Church, so they were somewhat familiar with what they were seeing. Since it was the Paschal season, the icon of the Descent into Hades was in a prominent place of honor on the analogion and, therefore, caught the eye of the minister’s wife.

“Oh, what is that icon?” she asked.

“That depicts our Saviour’s Descent into Hades,” I responded.

“What’s that all about?” she asked, incredulously.

Embarrassed by his wife’s reaction, the minister glanced at me nervously, and then back at his wife, and said,

“Why yes, dear. You know about that, of course. It’s mentioned in one of the Epistles of Peter.”

Ah! if looks could kill, the minister would have been charged with homicide! Talk about awkward moments.

It became obvious that the teaching about our Saviour’s descent to Sheol, the place of the dead, is not a prominent feature in Protestant Sunday schools.

Yet, as we mentioned above, it is clearly cited in the New Testament:

“For Christ also hath once suffered for our sins. He, the just, suffered for the unjust, that He might bring us to God. In the body, He was put to death; in the spirit, He was brought to life. And in the spirit He went and preached to the spirits that were imprisoned, who formerly had not obeyed….” (I Peter 3:18-20)

Furthermore, this event is also clearly prophesied in the Old Testament. In the Church’s services, one prominent element is the “Polyeleos” of Matins. One portion of the Polyeleos is a selection of verses from the Psalms of the Prophet David appropriate for each major feast. For the Feast of Thomas Sunday, the Resurrection of Christ is the major event being celebrated, of course, and these are some of the Psalmic verses that we hear in the Polyeleos:

“As for them that sit in darkness and the shadow of death. Fettered with beggary and iron. They cried unto the Lord in their affliction. And out of their distresses He saved them. And He brought them out of darkness and the shadow of death. For He shattered the gates of brass. And brake the bars of iron. And He delivered them from their corruption. And their bonds He brake asunder. To hear the groaning of them that be in fetters. To loose the sons of the slain.”

“He brought them out of darkness and the shadow of death.” All these Old Testament verses refer to our Saviour, “the fierce Man of war” spoken of in the Wisdom of Solomon, who “leaped out of Heaven” into a “land of destruction” to redeem mankind and lead the captive souls in Hades “out of darkness and the shadow of death.”

In the Book of Job, God speaks to Job out of a whirlwind and asks him:

“Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? tell me now, if thou hast knowledge, who set the measures of it, if thou knowest? Or who stretched a line upon it?….Or did I order the morning light in thy time?…Or didst thou take clay of the earth, and form a living creature, and set it with the power of speech upon the earth?…And do the gates of death open to thee for fear; and did the gate-keepers of Hades quake when they saw thee?” (Job 38:4-16)

The text is vivid and striking.

But there is a problem here: this last portion of the quotation from the Book of Job is quite different in the Protestant text. In the Revised Standard Version, for example, it reads as follows:

“Have the gates of death been revealed to you, or have you seen the gates of deep darkness?”

Very different indeed, and not much of a “prophecy” of the actual event. One might say that, as a prophecy of our Saviour’s descent into and destruction of Sheol, it has all the vigor and verve of an overcooked noodle.

In the article “Honour the Physician,” I recounted how my mother would not allow me to attend my playmate’s Protestant Bible class when I was a youngster in California. The reason she gave me for not allowing me to go was that “the Protestants had a different Bible” than we did. At the time, I thought she was just trying to find an excuse for not letting me go to the Bible class. But, as I wrote in that article, it turned out that she was right, and I came to understand this as I learned more about our Orthodox Christian faith. I wrote also in that article that there were two differences between our Holy Scriptures and the Scriptures that the Protestants use:

1) the books that we have in our Holy Scriptures are different, and

2) the interpretations that the Protestants give are different from the interpretations of the Church Fathers.

However, it turns out, there is also a third difference. Even within the books that we share in common with the non- Orthodox, the texts are different, as we can see, for example, in the abovementioned quotation from the Book of Job. One of the major reasons for these differences is that the Orthodox Church uses the Septuagint text of the Old Testament [see below], which was also the text used by the holy Apostles in the time of our Saviour.

The subject of the Descent into Hades – the “neutralization of the Netherworld” – is of vital importance. The implications of that event in Christ’s work of salvation has been sorely underestimated in the West; but that is a subject that will require yet another article. So, stay tuned.

The Septuagint Text ? A Footnote ?

What many people do not realize is that, as long as we can determine, there have been variants in the Scriptural texts as they have come down to us. Our readers will note that we have pointed out that the texts of the Old Testament that the Protestants and Roman Catholics use today are different from the Septuagint text that the Orthodox Church has used since the time of our Saviour. Why?

Some history may be useful here. By royal decree, the Septuagint text was prepared in the third century before Christ in Alexandria Egypt by the best Jewish scholars of the day.* At the time, Alexandria was the greatest center of learning in the known world, and its library was famous for its completeness and the valuable manuscripts it contained. The Septuagint translation was an occasion of great celebration, and a special day was set aside to commemorate this event in the Jewish community, which, for the most part, no longer spoke Hebrew, especially in the diaspora. (In Palestine the Jews spoke only Aramaic.) Now, with the Septuagint translation, the rabbis could instruct their people again easily in a language most of them spoke (Greek), but, in addition, they could make their faith more readily accessible to the pagan world around them. Consequently, the Septuagint was held in great esteem, and in the time of our Saviour, it was in wide use in the Jewish community (as the many quotations from it in the New Testament testify). What is also noteworthy is that Philo, one of the greatest Jewish scholars of antiquity, was also one of the foremost apologists for the Jewish religion among the pagans. Through the many tracts he wrote (all of them based on the Septuagint text), he led many thousands of pagans to convert to the Jewish faith. Yet, Philo, a contemporary of our Saviour, could not speak Hebrew. He knew only Greek.

With the appearance of Christianity, however, things began to change. The many thousands of pagans who formerly had converted to Judaism now began turning to the Christian faith. In addition, thousands of Jews also converted to Christianity. Through the work of the holy Apostles, the evangélion, the “good news” of our Saviour and His triumph over mankind’s last enemy – death – began spreading like wildfire throughout the Mediterranean world and beyond.

Furthermore, the Apostles were armed with proofs: the Old Testament prophecies that foretold of our Saviour’s coming. Thanks to the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, those prophecies were in a language almost everyone could understand. In the meantime, the whole Jewish world was shaken with a terrible catastrophe — the fall and complete destruction of Jerusalem in A. D. 70 by the Roman legions. This event, prophesied by our Saviour, caused utter consternation in the Jewish community, because, not only had the political center of the country vanished amidst inhuman atrocities and barbarity, but the Temple itself was gone! Literally, no stone was left upon a stone; the very center and heart of the Jewish faith had been ruthlessly cut out by the Romans, and even the Jewish priesthood was exterminated. The few shreds left of the city’s population were banished and the Jews began a long exile. In an attempt to restore some order out of this total devastation, around A. D. 90 or 100 a prestigious school of rabbis in the city of Jamnia (or Jabneh), which is some thirteen miles south of Jaffa, constituted a new Sanhedrin and discussed and determined the canon of the Old Testament. In view of the fact that the Septuagint was being used so extensively (and effectively) by the “new faith” (Christianity) in winning many thousands of converts from paganism and from the Jewish people themselves, it was resolved by the rabbinical school to condemn the Septuagint text and forbid its use among the Jews. The day which had been formerly been set aside as a day of celebration commemorating the translation of the Septuagint was now declared a day of mourning. Philo’s valuable tracts in defense of the Jewish faith were renounced as well, since they were based on the Septuagint translation.

The Old Testament text used today by non-Orthodox Christians is the Masoretic text, which was prepared by Jewish scholars in the centuries after Christ. When they picked among the many variant texts to prepare their own version of the Old Testament, these Jewish scholars, as might be readily understood, had an already decided bias against any Scriptural variant that might lend itself to a Christian interpretation. As the centuries passed, those variant texts not used by the rabbis fell by the wayside, or were usually destroyed, and thus, about a millennium after Christ, these scholars finally arrived at what is now known as the Masoretic text.

With the discovery of the Dead Sea scrolls in the middle of the twentieth century, however, the numerous ancient variants in the Hebrew sacred texts came to light again, and, in many cases, the Septuagint text proved to reflect the original Hebrew text better than the text that has come down to us in the later Masoretic version.

Also, many ancient Hebrew words cannot be understood or even pronounced any longer. They can be translated and understood only with the help of the Septuagint.

Thanks to the Dead Sea scrolls, the Septuagint text is now held in far greater esteem among non-Orthodox scholars than it was even a few years ago. The Septuagint text may have its own problems, but it represents an ancient and authentic Hebrew tradition. For centuries, it was beloved and celebrated by the Jewish people, and that is one of the reasons why it was, and still is, espoused and revered by the Christian Church.

Part Two can be viewed by clicking here.

Source

________

*We say “by royal decree” because, initially, the Jews were opposed to havingtheir sacred texts “defiled” by having them translated into a Gentile language. So, it required a decree by Ptolemy to have this work accomplished. According to ancient sources, the text used for the work of translation was supplied by the High Priest in Jerusalem.

3. THE CASE OF THE MISSING PROPHET

3. THE CASE OF THE MISSING PROPHET Preface

Preface