Who among us has not heard or repeated such phrases as: “vanity of vanities, all is vanity,” “the wind returneth again according to his circuits,” or “there is no new thing under the sun”? Many people know that these are from the Book of Ecclesiastes (or, The Preacher) in the Bible. In most cases, those who have read this book enjoy its melancholy poetry with its vivid, surprising imagery. Others wonder what is Christian about this book and why the Church has accepted it as one of its sacred texts.

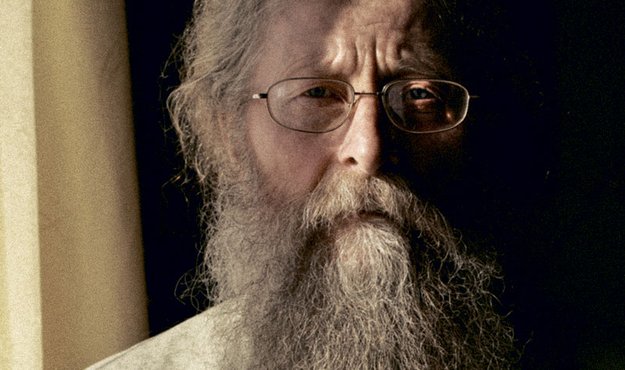

Quite brief compared to other Old Testament texts, Ecclesiastes (Qoheleth in Hebrew) was studied and commented on by the Holy Fathers of the Church; many volumes of modern studies have likewise been dedicated to it. We will discuss it here with Archpriest Gennady Fast, rector of the Church of Sts. Constantine and Helen in Abakan (capital of the Republic of Khakassia, Russia), biblical scholar, and author of many books about the Old Testament, including the recently published Commentary on the Book of Ecclesiastes [in Russian, 2009].

Archpriest Gennady Fast was born in 1954 in the Novosibirsk Oblast (in Siberia) into a deeply religious Lutheran family of exiled Russian Germans and was named Heinrich. After being expelled from Karaganda State University for his religious convictions, he studied physics at Tomsk University and later worked on the faculty of theoretical physics. Before graduating from university he converted to Orthodoxy and was baptized with the name Gennady. After being expelled from Tomsk University, he became a priest. He served in Tuva, in the Kemerovo Oblast, and in the Krasnoyarsk Krai. For many years he was rector of the ancient Dormition Church in Yeniseisk. He has trained scores of Siberian priests. He was, and remains, one of today’s most outstanding and well-known Orthodox missionaries. He is a biblical scholar and author of a number of books that have received wide distribution. At present he is rector of the Church of Sts. Constantine and Helen in Abakan.

Fr. Gennady Fast

Fr. Gennady, let us begin with authorship. Many of our readers will be surprised by the claim that the author of Ecclesiastes is the wise King Solomon, son of King David and builder of the Jerusalem Temple; in other words, that the unnamed Preacher and Solomon are one and the same person. One learns from your commentary that in his old age Solomon left his royal palace and his riches, dressed in rags, took up his staff, and went wandering along the roads, contemplating the vanity of all earthly things. Yet this is not in the Bible, just as there is no indication of Solomonic authorship.

In 3 [1] Kings 11, it says that Solomon died and was buried in Jerusalem. Moreover, he died under unfortunate circumstances: under the influence of his wives, he fell into idolatry and provoked God’s wrath. It was only for the sake of David, Solomon’s father, that the Lord spared Israel and Jerusalem in those days. Nowhere is it written that Asmodeus cast Solomon from the Holy City and that he set out wandering along the roads…

Indeed, there is a theory that Ecclesiastes came into being after the Babylonian captivity and was written by a later Hellenized Jew. This is due in part to the author’s philosophical inclination, which is much more characteristic of the culture of Greek antiquity than of Jewish culture. Likewise, philological analysis of the text forces one to consider a later origin. But this hypothesis can neither be proven nor disproven. Personally, I hold to the traditional, patristic point of view that the author of Ecclesiastes is Solomon. In patristic literature, Ecclesiastes was always viewed as being King Solomon’s repentance, the book he wrote after committing idolatry.

As far as the wandering along the roads with a staff is concerned, this is an ancient Judaic tradition contained in the Haggadah. The Holy Fathers accepted ancient Judaic traditions, many of which passed into patristic literature. I made use of this image – that of the stranger-king, of the king who rejects his kingdom for a pauper’s bundle – as a backdrop for reflecting on Ecclesiastes-Qoheleth. I think that this book could have arisen in just this way.

Yet there are no penitential motives in the text of Ecclesiastes, such as David’s Psalm 50…

Yes, this is not David’s repentance! This is more likely a philosopher’s repentance, a reexamination of his entire life. The word “repentance” is here best used in the Greek sense: metanoia, turnabout, change. There were several turnabouts in Solomon’s life: his ardent love for God and Divine Wisdom in his youth; his active life in adulthood; and later, towards the end of his life, a surfeit of wealth and pleasure leading to questionable actions. We do not entirely know how deeply he fell into idolatry, but it is clear that he became bogged down by his polygamy and flirted with paganism. He was later overtaken not by the heartfelt contrition of his father David, but by a certain philosophical reevaluation of his existence.

So I was great, and increased more than all that were before me in Jerusalem: also my wisdom remained with me. And whatsoever my eyes desired I kept not from them; I withheld not my heart from any joy: for my heart rejoiced in all my labour; and this was my portion of all my labour. Then I looked on all the works that my hands had wrought, and on the labour that I had laboured to do: and behold, all was vanity and vexation of spirit, and there was no profit under the sun (Ecclesiastes 2:9-11).

Why did the question of the meaning of life arise in him, who was fully a man of the Old Testament? Why did it not arise among Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, or among Moses, Joshua, Samuel, and David, among others?

This is like asking why it was specifically Einstein who came up with the theory of relativity. Or why was it was specifically Pushkin who wrote Eugene Onegin. People are different; each has his own path and calling on this earth. The righteous of the Old Testament you list were deeply religious, but none of them chose wisdom as their main principle of life; they did not ask God for an understanding heart, as did Solomon at Gibeon (cf. 3 [1] Kings 3:9). Having received wisdom from God, Solomon served it all his life – and it is precisely this that never changed! He served wisdom when judging people, when he composed the Song of Songs, when he wrote Proverbs – the entire body of Solomonic books might be called books of wisdom. Therefore, it is not surprising that the philosophical problem of the overall meaning of life would arise specifically for Solomon.

Then said I in my heart, As it happeneth to the fool, so it happeneth even to me, and why was I then more wise? Then I said in my heart, that this also is vanity. For there is no remembrance of the wise more than of the fool for ever; seeing that which now is, in the days to come shall be forgotten. And how dieth the wise man? as the fool (Ecclesiastes 2:15-16).

The Righteous Prophet and King Solomon

But this might also be put differently. Solomon’s precursors in sacred history, the righteous of the Old Testament, were devoid of painful reflection. They knew how to live. They loved life. They were neither oppressed by its finitude nor frightened by death: they died with remarkable calm and had very little interest in what would happen to them after their deaths, or whether there would be anything at all. They were joyful when children were born to them, and it never entered their heads to ask: why was this child born, given that it will die anyway? When all is said and done, they were healthy! Compared to them, Solomon seems like a tortured intellectual, almost Chekhovian…

Indeed, Solomon’s predecessors did not resemble him. They lived by faith and love for live, with which they were perfectly satisfied. They were not philosophers. The philosophical view of life is generally uncharacteristic of ancient Israel. The books of the Old Testament are not philosophical; they are historical and prophetic. The Ecclesiast is something of an exception. He really does seem to belong to another culture. This has provided the grounds for biblical criticism to doubt the identification of the Ecclesiast with Solomon. The Ecclesiast or Qoheleth – or, as we believe, Solomon – is someone who may not have had a deep religiosity. The Song of Songs makes no mention of the Creator. The Wisdom of Solomon could, with light editing, be used by atheists. God is mentioned there, but He is not central, and it is not He who governs all things. In this sense, Solomon is consistent: this is who he is, and he could be no other way. It is no accident that you draw a parallel between him and the Russian intelligentsia of the nineteenth century. That century we had St. Philaret of Moscow, the Optina Elders, Theophan the Recluse and, finally, Gogol and Dostoevsky, who led their readers – if not always evenly and smoothly – along the path of the Orthodox faith. We also had Leo Tolstoy, however. It is very hard to answer the question of what, for the Count, was lacking in Orthodoxy, or why he had so much dislike for it. In the case of the Qoheleth, we can say that God made us of him – and, by the way, God also made use of Tolstoy. I know many people who read Tolstoy during the Soviet era, because his work was easily accessible, and through him began to reflect on deeper spiritual problems. And this served as the impetus, in the long run, for them to come to Orthodoxy. On the contrary, I do not know of a single Orthodox person who, after having read Tolstoy, left Orthodoxy for Tolstoyanism. If Tolstoy had only known!

I said in my heart concerning the estate of the sons of men, that God might manifest them, and that they might see that they themselves are beasts. For that which befalleth the sons of men befalleth beasts; even one thing befalleth them: as the one dieth, so dieth the other; yea, they have all one breath, so that a man hath no pre-eminence above a beast: for all is vanity(Ecclesiastes 3:18-19).

Why, and on what religious basis, did Ecclesiastes become what it is?

It became what it is because, in essence, it is asking a question. Ecclesiastes asks the question, the Gospel gives the answer. Neither Moses nor David asks questions; they are satisfied with what they receive directly from God. The Prophet Elias says: The Lord God of Israel liveth, before whom I stand (3 [1] Kings 17:1). What questions can he possibly have? But with Solomon… He was not an atheist, of course; he was a believing person, but he came close to the very edge of the abyss in which there is no God. At certain moments for him it is as if God vanishes. But God needs just such a person so that the question might be asked. Solomon is ruthlessly candid, and cannot find comfort in such customary phrases as “God will provide…” or “It’s all God’s will…”

He is, by the way, not entirely alone. The long-suffering Job likewise asks questions and likewise finds no comfort in such phrases. Nor does the Prophet Habakkuk find comfort in them: he climbs the tower and offers his complaint to God. But Solomon, unlike Job and Habakkuk, has no complaint for God. Perhaps they had these complaints because they felt God so closely. In comparison with them, Solomon is in some sense a wordly person; his complaint is not directed to God, but to a life that is completely meaningless. He had everything that this life can offer: immeasurable wealth, power, glory, honor – but now he sees no meaning in any of it. Ecclesiastes is not even about the meaning of life; it is about life’s meaninglessness. The author has an honest view, he is free of all self-delusion, he sees this meaninglessness without embellishment. Where is divine revelation in Ecclesiastes? Here is the paradox: it is in the fact that it leaves one without God. It allows one to see clearly what life without God is like. That is why this text is so dramatic, why there is the strain, intensity, and drama of a human soul that has lost all meaning.

I was struck by a phrase from your book: “Only in the desert of Ecclesiastes can one find the oasis of the Gospel.” However, this too is perplexing. Is it really only possible to approach God through the condition of the Ecclesiast, through the experience of meaninglessness and emptiness? Are there no other ways?

You are not the only one who is perplexed. One journalist, who was outraged by my statement, said: neither Sergius of Radonezh, nor Seraphim of Sarov, nor John of Kronstadt needed any such desert in order to score the source of living water. But these words, which I have nonetheless left in the book, do not necessarily imply a chronological order: first the experience of desertedness, emptiness, meaninglessness – and then the Gospel. It happens in this order with some, but not with all. The saints mentioned here experienced the Ecclesiast’s desert in this sense: they experienced deeply the vanity and futility of this world and therefore renounced it. Otherwise they would not have had the revelations that were given to them. Whoever is perfectly satisfied with this world will never become a Sergius or a Seraphim, even if he knows the entire Psalter by heart. The emptiness of this world without God needs to be experienced inwardly so that it can later be filled by God.

Ecclesiastes is very current, very relevant to our times. It defines someone who participates in the consumer race, in the pursuit of pleasure, success, and empty amusements. Today I know people who have come to Christianity specifically through the Preacher’s book. By reading it one sees the godlessness of the world and sets off in search of God, finding Him in the Gospel. It is a great pity, of course, that people (the faithful included, alas!) today read so little and prefer lighter reading. But Ecclesiastes remains very much in demand and is still read, even if it is not wholly understood.

For God giveth to a man that is good in his sight, wisdom, and knowledge, and joy: but to the sinner he giveth travail, to gather and to heap up, that he may give to him that is good before God. This also is vanity and vexation of spirit (Ecclesiastes 2:26).

What is necessary in order to understand Ecclesiastes?

A key of sorts to Ecclesiastes is the Hebrew word yitron, which appears nowhere else in the Bible. It means “remainder” or “profit.” It is what we sometimes call the bottom line. It answers the question: “With all this, what do we really have left?” The Ecclesiast needs an answer to this question and so puts everything to the test: wealth, poverty, women, wine, creative work, power, even piety. But the bottom line is that there is nothing left: everything is “vanity of vanities” and vexation of spirit.

For what hath man of all his labour, and of the vexation of his heart, wherein he hath laboured under the sun? For all his days are sorrows, and his travail grief; yea, his heart taketh not rest in the night. This is also vanity. There is nothing better for a man, than that he should eat and drink, and that he should make his soul enjoy good in his labour. This also I saw, that it was from the hand of God (Ecclesiastes 2:22-24).

But how is there nothing left? Solomon built the Temple, after all! In the Temple a miracle was manifest on the very first day and Solomon prayed for his people for generations to come (cf. 3 [1] Kings 8) – these pages cannot be forgotten! The Temple was still standing at that moment in history. It had not yet been destroyed!

The Temple was standing. But this did not change anything. This is often the case in life. When we read Solomon’s prayer at the dedication of the Temple, we see that the Temple was filled with the divine presence – truly the Shekhinah. But then nothing was left. Solomon-Ecclesiast does not even mention the Temple a single time! (This, incidentally, causes biblical critics to doubt King Solomon’s authorship. But, in some sense, this is of no importance to us.) The Apostle Paul warns us that it is quite possible to preach to others and remain a castaway oneself (cf. 1 Corinthians 9:27). Such tragedies happen to people, even to priests – there is such a thing as burnout. I have seen burned-out priests, among whom were men who were talented, intelligent, and by no means devoid of moral qualities. They had all been quite zealous in their time. But then some inner disillusionment came along and the mundane crept into their lives. The same thing happened with the Ecclesiast. He built the Temple, but he did not gain the higher good – the yitron.

But a burned-out priest most likely has himself to blame, and so too with the Ecclesiast…

Perhaps. If Solomon had always maintained the temperament he had on the day the Temple was dedicated, would idols have appeared in Jerusalem? But they did appear. Yes, the Ecclesiast’s story is that of a fall or emptying. He was full and became empty. For nothing under the sun has this yitron. For in fact, yitron is what is above the sun.

But besides the word yitron, there is another key word needed for understanding Ecclesiastes: tov. Unlike the first word, it is common in both ancient Hebrew and in Holy Scripture, beginning with the first chapters of Genesis. It means “good” or “fine.” That which is good is tov. Everything, as we have already said, that Solomon tested – riches, glory, women, wine, labor, piety – was in fact good, tov. Reading the text of Ecclesiastes, we see how he repeatedly tries to climb to the summit in order to reach the desired yitron, but for some reason is unable. Not wanting to fall all the way to the bottom, where there is sin and perdition, he settles into a kind of average human happiness, into this tov. But for some reason, the philosopher cannot stay for long in this common human happiness. Again clambering to the summit, he again falls down and looks for comfort in the common tov, which he does not find. It is this hovering between the ordinary good and the loftier, imperishable good that defines the state of soul of the Qoheleth, the philosopher.

Behold that which I have seen: it is good and comely for one to eat and to drink, and to enjoy the good of all his labor that he taketh under the sun all the days of his life, which God giveth him: for it is his portion (Ecclesiastes 5:18).

Was it not this drama that attracted Christian ascetics to Ecclesiastes?

It served as a sort of justification for what they were doing. After all, Ecclesiastes is a book about the meaninglessness of life in its more positive aspects. Note that the author does not reflect on suffering, illness, crime, war, and so on. He reflects on the normal, positive condition of man – what is normally considered happiness. Happiness is that same tov in which there is no yitron. In the Gospel there is no concept of happiness whatsoever; rather, there is a different concept: blessedness. Blessedness is yitron, a loftier attainment. Remember the rich youth who went away from Christ sorrowful (cf. Matthew 19:16-22; Mark 10:17-22; Luke 18:18-23)? He was offered tov – average wellbeing and piety (“keep the commandments”). But this did not satisfy him. But to part with his wellbeing and wealth for the sake of blessedness and treasure in heaven – this he could not do (cf. Matthew 19:21).

Christian ascetics consciously gave up the world in its vain manifestations, denying themselves seemingly blameless and God-created pleasures – but this was not a rejection of sin. This was a rejection of tov, of the good, because in this good, there is no yitron, the highest good.

You dedicate an entire chapter of your book to the Ecclesiast’s antimonies, the most famous of which is: A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together (Ecclesiastes 3:5). What is their moral and spiritual meaning?

To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven (Ecclesiastes 3:1). People often do not know which season it now is, or they think that an entire season is for one thing alone. But life is dialectical; the laws of dialectics have never been repealed. Someone who is a Christian, who lives in the Holy Spirit, should be able to feel the season with particular sensitivity. His actions might be contradictory: he might punish or forgive, strike out or give healing. There is a well-known incident from the life of St. Luke (Voyno-Yasenetsky) of Crimea: he saw some members of the Komsomol [Young Communist League] placing a ladder against the wall of a church in order to climb onto the roof and remove the cross. The saint wrathfully shook the ladder and they fell down and were hurt. Then he took them to the hospital and treated them: to everything there is a season. Or take Admiral Ushakov, about whom many people still ask why he was glorified among the saints and where his holiness lies. His cannons destroyed the Turkish squadron and the Turks started drowning – so he sent his sailors out on lifeboats to saves them and pull them out of the water: it was the season to show mercy. Divine Sophia, Wisdom, is manifest in a person when he knows the season.

Ecclesiastes has a very powerful moral charge. Its author is a very moral person – in other words, a man of righteousness. For him a wise life is a righteous life. But there is also the assertion that righteousness is meaningless. How do these things go together?

This is the Ecclesiast’s tragedy! He is unable to live immorally, he encourages piety, but all the while he sees the futility of piety without God. Here we can call to mind our Communists, among whom were people of high morals, people who gave their life in the war… But those whom I was able to encounter could no longer believe in any sort of communism. They urged people to work, to live honorably and according to the laws of communist morality, and they did not feel any discomfort in this – so long as they did not look inward, so long as they were not inclined to Russian soul-searching. They were like the Preacher, which again confirms that every time and generation can see itself in the Ecclesiast.

God does not lose people who have lost Him. Someone might not have God and has emptiness instead, but God does not leave him because he lives morally; he neither can nor wants to fall below a certain moral level. In principle, this is characteristic of any person; even criminals create their own moral code, which they call “living by the rules.”

I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happenteth to them all. For man also knoweth not his time: as the fishes that are taken in an evil net, and as the birds that are caught in the snare; so are the sons of men snared in an evil time, when it falleth suddenly upon them (Ecclesiastes 9:11-12).

Solomon was a wise man and a philosopher, but not a prophet… Yet you write that there is testimony concerning the coming Messiah in his book…

There is a text that allows for messianic interpretation, in chapter 4, beginning with verse 13, about the child who is born poor into his kingdom: There is no end of all the people, even of all that have been before them: they also that come after shalt not rejoice in him. Surely this also is vanity and vexation of spirit (4:16).

But how is this messianic, if it is all vanity?

Many walk with this Child, with Christ – this is the mass conversion of the nations to Christianity. They that come after that will not rejoice – this is apostasy, growing cool, falling away. For how many nations today is faith in Christ only a vestige, only the remains of a tradition? Christmas, the beloved winter holiday for families, no longer has anything to do with Christ. We live in an epoch that is called post-Christian… The text of Ecclesiastes shows that Christianity itself is no exception, that its historical path follows the same cycle: rise is followed by decline, ardor by frigidity. Although ultimately the gates of hell shall not prevail against the Church (cf. Matthew 16:18) and the Bridegroom will come for His bride. Everything done for the Lord’s sake is good; Orthodox empires with magnificent churches are good. But then enemies come, or rebellion breaks out, and the churches are emptied and destroyed. The way out of this cycle is only the Eighth Day, when the cycle will be completed with the appearance of the Lord in glory. But for us, living today, the way out is holiness, it is the Kingdom of God that we await as coming, but which we have already now. When in the Liturgy we exclaim “Blessed is the Kingdom,” we are blessing the Kingdom that is here and now, in which we are. This is the way out of the vicious circle, including the cycle of Christian history, that Solomon did not see. Ultimately, yitron is the Lord Himself – the Lord, Who is everywhere and in everything. An ancient Paterikon tells the story of a monk who could attend the Paschal services because every year he was assigned to the kitchen. This was a serious deprivation for him, and he dreamed of at least hearing how they sang “Christ is Risen.” But the Lord consoled him with apples from Paradise, with which he was able to treat the brethren returning from the service in the morning.

Interview conducted by Marina Biriukova.

thanks to:

http://www.pravmir.com/ecclesiastes-asks-the-question-the-gospel-gives-the-answer/